Miles

Long COVID presents persistent challenges for individuals struggling with energy regulation and recovery. This project ‘Miles: Post-COVID’ aimed to provide adaptive support for people with long COVID.

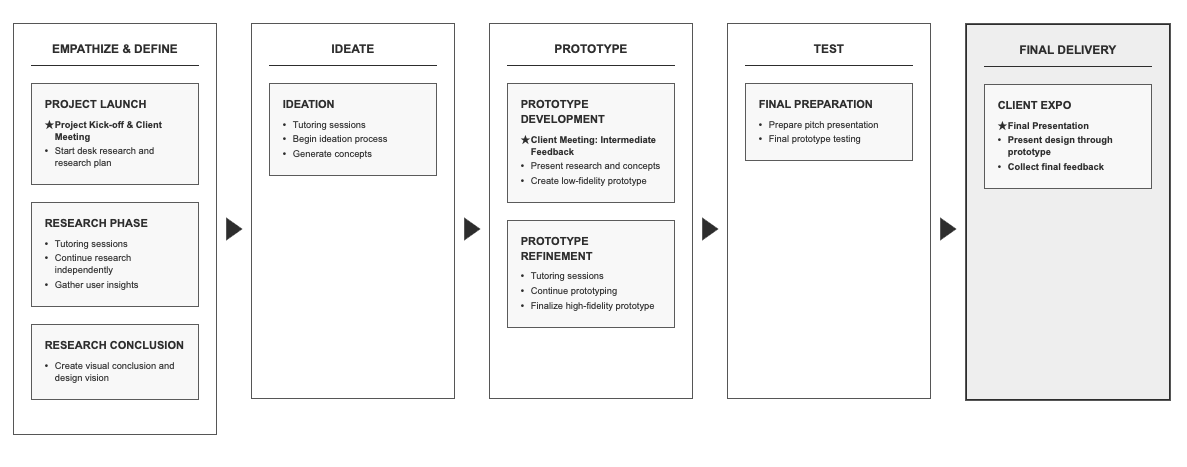

Timeline

04.2025 - 07.2025

Client

Stichting Bestaanskracht

Role

Lecturer UX Design Lead

Design challenge

design a customisable app that supports people with Long COVID for recovery

Existing apps are often unadapted to their unpredictable recovery journeys

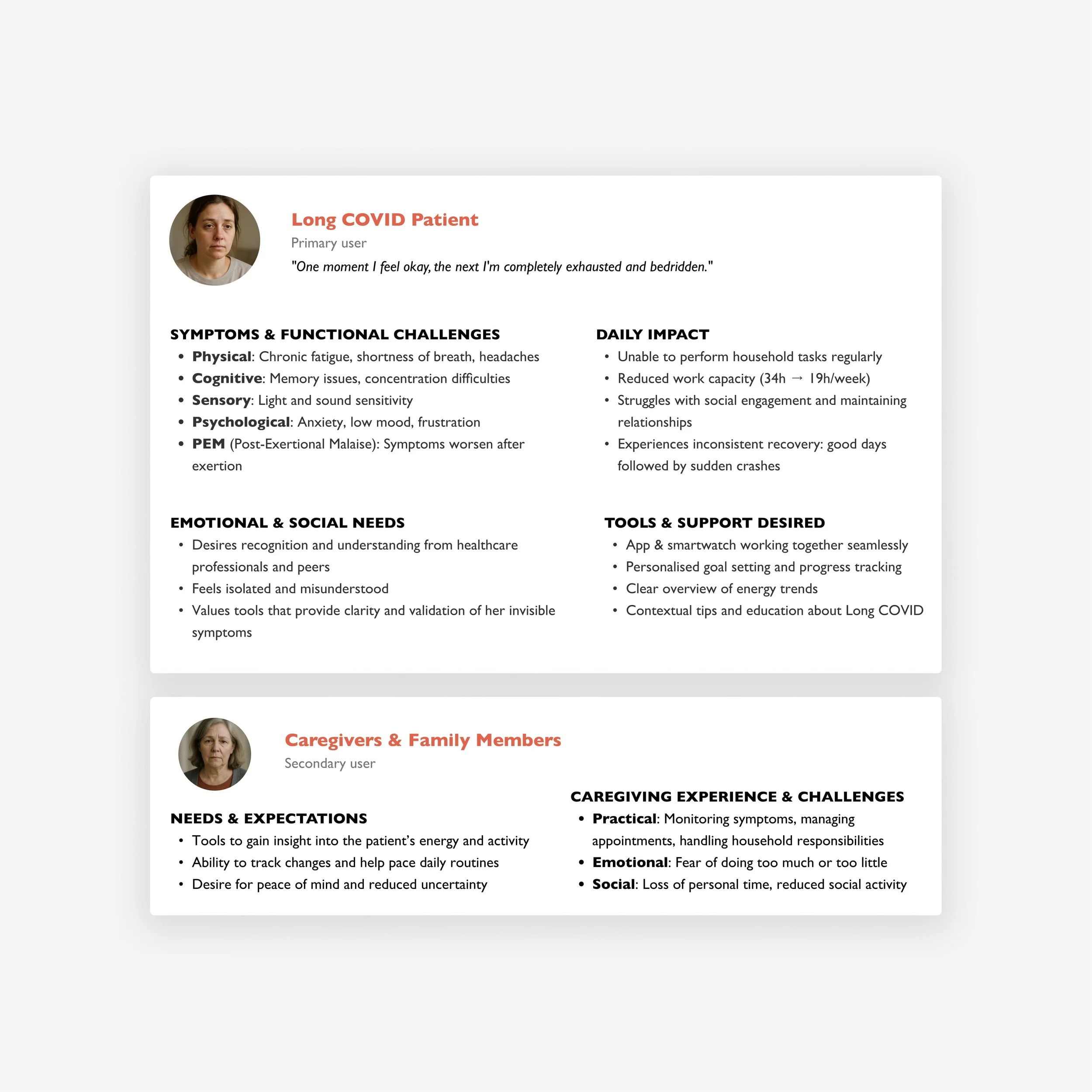

The target user- people with long COVID- often experience severe fatigue, cognitive challenges, emotional instability, and fluctuating symptoms.

project overview

13 first-year UX Design students at The Hague University of Applied Sciences joined the collaboration project with Stichting Bestaanskracht. While keeping in touch with target users, we used the Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) model built upon the organisation’s previous initiatives to support our design process.

Results

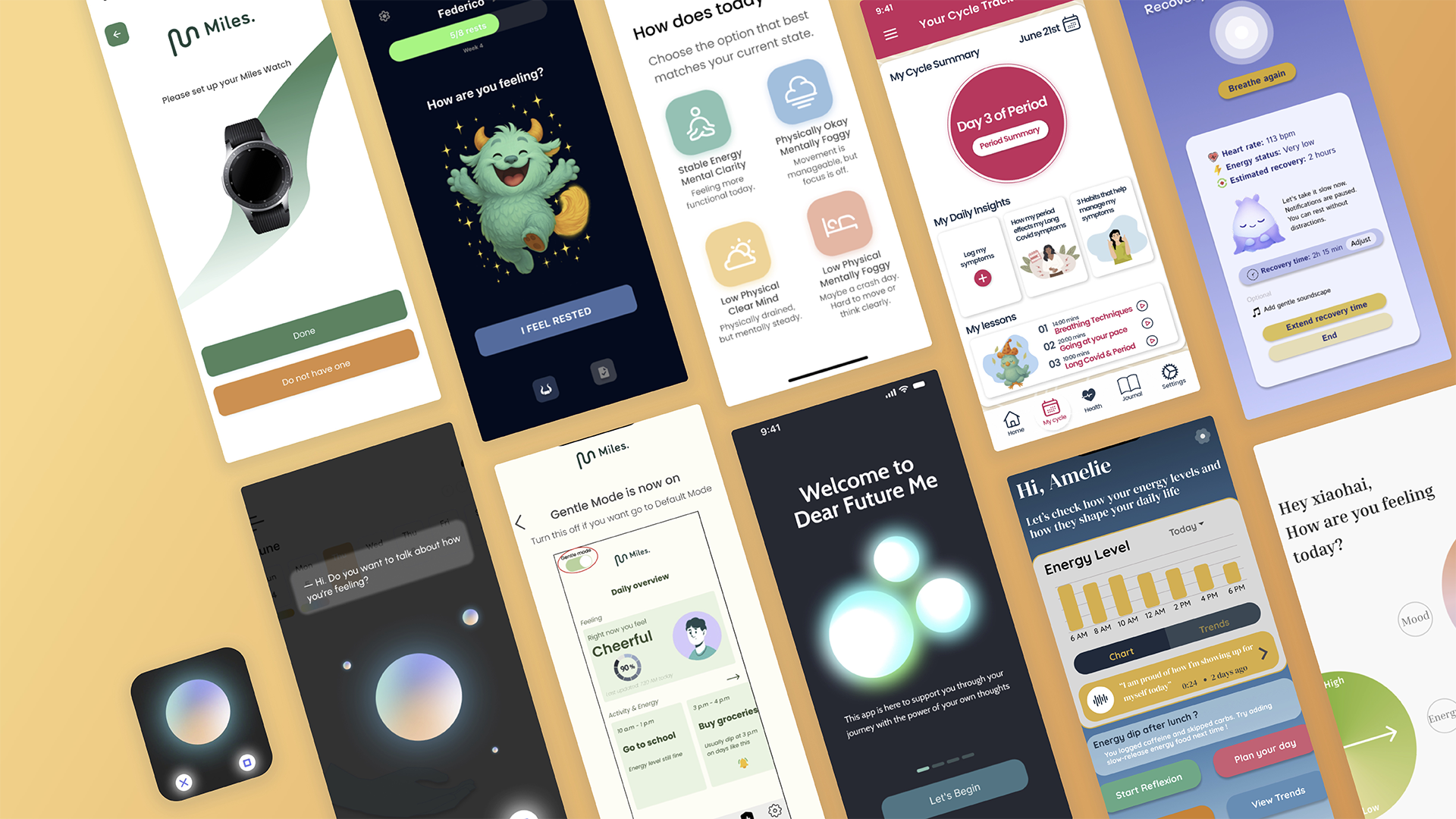

13 student-designed tools (e.g., voice diaries, pacing planners, future-self messengers)

Emphasised clarity, flexibility, and emotional validation as a design function

Key student insight: "Designing for energy limits is about listening more than solving."

My Role as a lecturer & UX Lead

01

Guided students to gentle pacing, emotional clarity, and invisible symptom design suited for vulnerable users (e.g., voice notes, day-in-the-life mapping)

02

Introduced how to integrate the RAG model into their design process and how to create the right prompt to access the desired information for each phase, from research to test.

03

Led weekly coaching that balanced UX rigour with empathy coaching, helping students define emotional tone early

04

Supported each student through iterative testing, with feedback loops focused on tone sensitivity and interface calmness

research

To ensure this course was grounded in lived experiences, students conducted first-hand research with the long COVID patients affected by Long COVID and their support networks. In total, over 90 distinct user insights were synthesised across 13 students. Below shows our research methodologies and the overview of the user personas created by the students.

Fieldwork Methods

Each student team engaged in exploratory research through qualitative methods such as:

1:1 semi-structured interviews (avg. n = 1 per student due to the difficulty in the participant recruitment)

Surveys & self-report diaries

User journey mapping to capture fatigue patterns

Card sorting and pattern recognition workshops

Emotional touchpoint identification

Integrating RAG Model

Not many information was provided at the beginning, such as the features in the prototypes from the previous initiatives, original quotes from the users and the caretakers, etc. That’s where this RAG model can intervene to support the projects. As a lecturer, I provided example prompts as below:

Immerse yourself as a Long COVID patient suffered from the symptoms for 5 years. Generate a user journey map when using the current app Miles. 1) Include emotional changes, social interactions, digital interactions, quotes, frustrations and needs. 2) Add the references to each part.

Can you explain the user journey of the Miles NAH app in a bullet list? Highlight the relevance of the feature to the target user.

If you (this RAG model) were a human being, how would you look like? Visualise yourself.

This was a question to inspire the students’ regarding how to ask ‘different’ questions.

key insights

-

This is because users fear crashing mid-task and often build their routines around bodily signals rather than time.

-

The target users prefer layered options like A-B-C plans and adaptive suggestions over rigid schedules.

-

Peer support and empathetic design help users feel seen and resilient.

-

This is because cluttered interfaces create overload, while users thrive with calm, minimal designs and intuitive defaults.

-

It enables more empathetic support through gentle, real-time insights into energy and emotions.

-

It helps users detect early warning signs through non-alarming cues that foster calm and self-regulation.

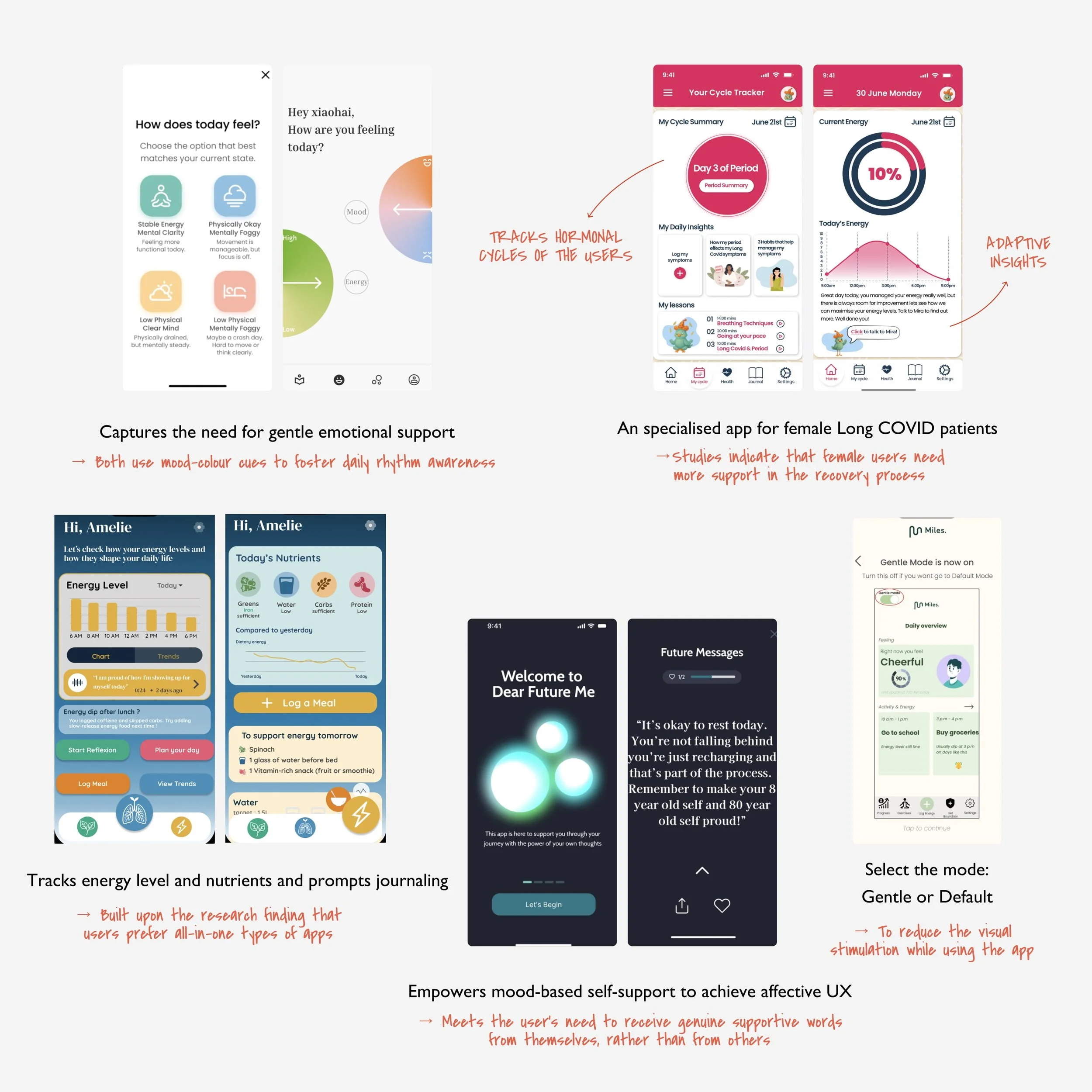

ideation

After the research phase, the students were guided to iterate their prototypes. Eventually, 13 outcomes were created.

The bar graph shows which key strategies from the given design challenge were applied.

Overview: Design Directions

Final Design

direction 1

Emotion-Driven Care & Expressive Design

This direction centres on emotional recovery and self-expression, using journaling, mood tracking, and soft interaction styles to help users process their experiences and rebuild a sense of control.

Key Characteristics

Emotional metaphors and avatar-based systems

Journaling, reflective prompts, and mood-responsive UIs

Emphasises identity, empathy, and emotional validation

direction 02

Data-Aided Agency & Cognitive Relief

This direction emphasises clarity and cognitive offloading through structured tools, helping users plan, track, and communicate their condition with minimal effort and emotional strain.

Key Characteristics

Energy scheduling, routine pacing, and daily plans

Visual summaries and emotional check-ins

Emphasises simplicity, insight, and low-input structure

reflection

as a lecturer & a design lead

Student work demonstrated strong alignment with user insights, especially around emotion, autonomy, and simplification. From there, the client rated our projects- highly positive (8 out of 10 stars). Particularly, the client showed a great satisfaction towards the diversity of the ideas.

This was my first time using the RAG model within the design project. I’m familiar with prompt engineering, and it was easy for me to access the information I aimed for. However, the students were not yet comfortable with using this model, and that made me guide the students on how to effectively communicate with this AI model. As a teacher, this is not a recommended action, but then, if talking to AI is becoming a demanding skill in the design scene, shouldn’t we also talk about it at least?

Overall, I found that using this model is efficient as it can simulate the users’ behaviours based on the collected information. Also, this model supported the students in executing user testing as they had issues with recruiting users for their activities. The prompt started with ‘Immerse yourself as a long COVID patient. Based on the given images and the flow I provided, 1) evaluate the experience based on this System Usability Scale form (SUS) and 2) share the comments’. Although I am personally not sure about the validity of the information since we’re doing a ‘user-centred’ project, it has room for further development.

takeaways

Increase User Involvement in Evaluation

While students conducted strong early-stage research through interviews and journey mapping, fewer users were involved during testing phases, limiting the depth of feedback on tone, usability, and emotional resonance.

→ It’s needed to integrate lightweight user validation methods (e.g. guided prototype walk-throughs, remote emotional feedback journaling), to gather deeper responses without burdening participants.

Bridge Emotional Design with Functional Routines

Many students successfully explored emotional wellbeing, but some concepts lacked concrete functionality for daily use (e.g. how pacing tools integrate into a morning routine).

→ Context-mapping exercises can ask students to embed their ideas into users’ real schedules, testing for fit across energy highs and lows.